BACK

TO

MAIN

What now? Words fail. There are times when even they fail. Is that not so, Willie, that even words fail at times? What is one to do then until they come again? Brush and comb the hair if it has not been done, or trim the nails if they are in need of trimming. These things tide one over. Bless you, Willie. Just to know that in theory you can hear me, even though in fact you don’t is all I need. Not to say anything I would not wish you to hear or liable to cause you pain. Not to be just babbling away on trust, as it were, not knowing, and something gnawing at me. Doubt. Here. Abouts. There is of course the bag. There will always be the bag. Even when you are gone

And yet it is perhaps a little to soon for my song. To sing a song too soon is a great mistake, I find. There is of course the bag. Could I enumerate its contents? Could I, if some kind person were to come along and ask, What have you got in that big black bag, Winnie? Give an exhaustive answer? No. The depths in particular, who knows what treasures. What comforts. Yes, there is the bag. But something tells me, Do not overdo the bag, Winnie, make use of it of course, let it help you… along when stuck, by all means, but cast your mind forward, cast your mind forward, Winnie, to the time when words must fail – and do not overdo the bag. Perhaps just one quick dip. (revolver) You again! Oh I suppose it’s a comfort to know you’re there, but I’m tired of you. And now? Is gravity what it was? I fancy not. Yes, the feeling more and more that if I were not held – in this way – I would simply float up into the blue. Don’t you ever have that feeling, Willie, of being sucked up? Don’t you have to cling on sometimes? You don’t? Ah well, natural laws, natural laws, I suppose it’s like everything else, it all depends on the creature you happen to be. All I can say is, for my part, for me, they are not what they were when I was young and… foolish and… beautiful… possibly… lovely… in a way…to look at. Forgive me, Willie, sorrow keeps breaking in. Ah well, what a joy to know you are there. I used to perspire freely. Now hardly at all.

The heat is much greater. The perspiration much less. That is what I find so wonderful. The way man adapts himself. To changing conditions. Oh yes, great mercies. I speak of the time when I was not yet caught – in this way – And I had my legs and the use of my legs, and could seek out a shady place, like you, when I was tired of the sun, or a sunny place when I was tired of the shade, like you - and they are all empty words.

FRANS TIMMERMANS

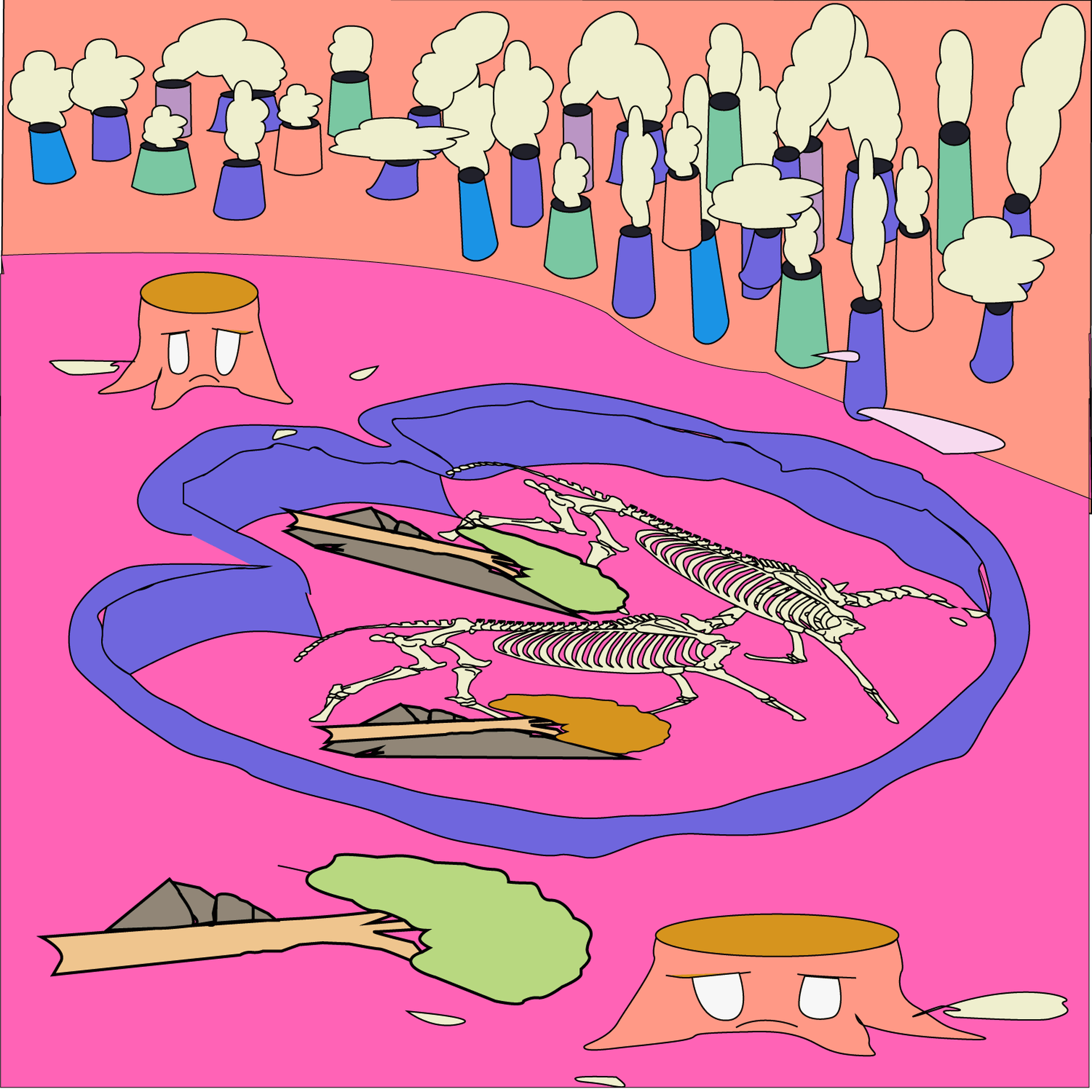

CO 2 neutral EU by 2050. Europe should be the first climate-neutral continent in the world.

“Before the crisis, companies still had the choice to wait with major adjustments, because it was actually going well. Now they are forced to restructure drastically, they have to look to the long term. They need money for that, from governments and the private sector. Large investors are fearful of so-called 'stranded assets', production resources of companies that are no longer worth anything in a climate-neutral future. That is the economic reality that has given us a boost. Meanwhile, public support for large government investments will only come if we can demonstrate that they lead to a sustainable industry for the future. ”

(If you look at demographic developments in Europe, the problem is not structurally too few jobs. The real problem is: the wrong jobs for the misqualified people. Youth unemployment will only be tackled if we help young people with skills training for the future economy. It is true that the Achilles heel of all our plans is the social side. But that's what politics is for. In the neoliberal world we seem to have forgotten that, but intervening to prevent wrong effects is what politics is all about! ”)

The biggest misconception is that if you don't do anything, everything will stay the same. Things change quickly, even if you don't do anything. The climate transition is not the problem, but the mistakes you make to get there. Our greatest risk is that the costs for industry will be much lower than those for individual households. We must prevent this with targeted policy. The question that worries people is: what's in it for me, am I part of this or is it a toy of the elites? If we do nothing and the climate crisis gets out of hand, the elites will take care of themselves.

'Coronavirus shows us it’s time to rethink everything. Let's start with education.'

George Monbiot

In an age in which we urgently need to cooperate, we are educated for individual success in competition with others. Governments tell us that the purpose of education is to get ahead of other people or, collectively, of other nations. The success of universities is measured partly by the starting salaries of their graduates. But nobody wins the human race. What we are encouraged to see as economic success ultimately means planetary ruin.

They say that pandora opened the box of evils and the evils went out in the world.

Only the hope was left in the box.

We think about this as if hope is the last thing we turn too as humans.

And that might very well be true.

But we tend to see it as a good thing, the only good thing.

But it was a box of evils, hope was side by side with death, sickness, and pain.

Maybe our hope is our curse, the true curse, if Pandora at least had let it out we wouldn’t be possessed by it.

Now we are victims of hope.

Today our problem lies—it seems—in the fact that we do not yet have ready narratives not only for the future, but even for a concrete now, for the ultra-rapid transformations of today’s world. We lack the language, we lack the points of view, the metaphors, the myths and new fables. Yet we do see frequent attempts to harness rusty, anachronistic narratives that cannot fit the future to imaginaries of the future, no doubt on the assumption that an old something is better than a new nothing, or trying in this way to deal

with the limitations of our own horizons. In a word, we lack new ways of telling the story of the world.

We live in a reality of polyphonic first-person narratives, and we are met from all sides with polyphonic noise. What I mean by first-person is the kind of tale that narrowly orbits the self of a teller who more or less directly just writes about herself and through herself. We have determined that this type of individualized point of view, this voice from the self, is the most natural, human and honest, even if it does abstain from a broader perspective. Narrating in the first person, so conceived, is weaving an absolutely unique pattern, the only one of its kind; it is having a sense of autonomy as an individual, being aware of yourself and your fate. Yet it also means building an opposition between the self and the world, and that opposition can be alienating at times.

Life is created by events, but it is only when we are able to interpret them, try to understand them and lend them meaning that they are transformed into experience. Events are facts, but experience is something inexpressibly different. It is experience, and not any event, that makes up the material of our lives. Experience is a fact that has been interpreted and situated in memory. It also refers to a certain foundation we have in our minds, to a deep structure of significations upon which we can unfurl our own lives

and examine them fully and carefully. I believe that myth performs the function of that structure.

The world is dying, and we are failing to notice. We fail to see that the world is becoming a collection of things and incidents, a lifeless expanse in which we move around lost and lonely, tossed here and there by somebody else’s decisions, constrained by an incomprehensible fate, a sense of being the plaything of the major forces of history or chance. Our spirituality is either vanishing or becoming superficial and ritualistic. Or else we are just becoming the followers of simple forces―physical, social, and economic―that move us around as if we were zombies. And in such a world we really are zombies.

On that note, the “house” in the film (ie, the colony) can certainly stand as a metaphor for coronavirus-era Iran: a pariah nation battling a pandemic under crippling US sanctions costing ordinary Iranians their lives at an alarming rate. In perhaps the film’s most harrowing scene, a schoolboy is asked to write a sentence on the blackboard with the word “house”. He thinks to himself before scrawling with his damaged fingers: “The house is black.”

The House Is Black has taken on even more meaning in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. For one, it can make those self-isolating appreciate what they have. Our pandemic will pass, but for the quarantined patients in the film, especially those with advanced leprosy, illness and isolation from the rest of society are facts of life. They have no recovery to look forward to, passing out their days in a slow decay. “I am poured out like water … as those who have long been dead,” Farrokhzad says in her voiceover. “On my eyelids is the shadow of death.”

Given the severity of our ecological crisis, perhaps we should be more ambitious than what Saez and Zucman propose. After all, nobody "deserves" extreme wealth. It’s not earned, it’s extracted – from underpaid workers, from nature, from monopoly power, from political capture and so on. We should have a democratic conversation about this: at what point does hoarding become not only socially unnecessary, but actively destructive? $100m? $10m? $5m?

The ecological crisis – and the science of planetary boundaries – focuses our attention on one simple, undeniable fact: that we live on a finite planet, and if we are going to survive the 21st century, then we need to learn to live on it together. Toward this end, we can take lessons from our ancestors. Anthropologists tell us that, for most of human history, most people lived in societies that were actively and intentionally egalitarian. They saw this as an adaptive technology. If you want to survive and thrive within any given ecosystem, you quickly realise that inequality is dangerous, and you take special precautions to guard against it. That’s the kind of thinking we need.

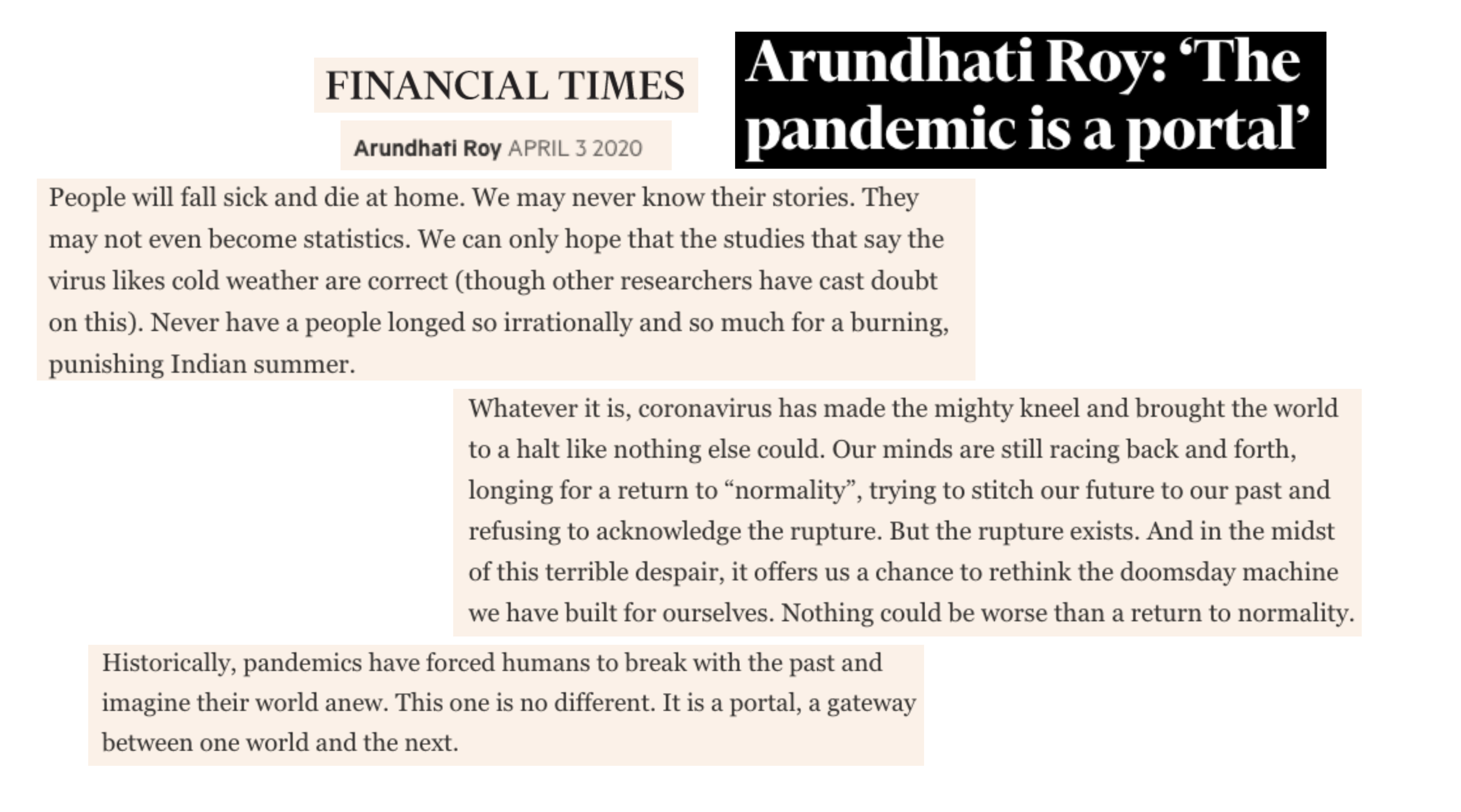

There is an extraordinary opening for this right now. The Covid-19 crisis has revealed the dangers of having an economy that’s out of balance with human need and the living world. People are ready for something different.

The danger of inequality by Jason Hickel

Flight to

nowhere

.

Escape

to nowhere

There is a world now,

And there was one before the pandemic.

Even though

We don’t feel that way…

Things can never be different

And we shouldn’t be opponent to the growth

Instead, we should

focus on endorsement

and eligibility

to work in prospects

and controversiality…

that our world is not

as versatile

as we might

have in our minds…

After all,

its the written on the wall

by strangers

from the past…

For people of different circumstances to live together in the same space is not easy.

It is increasingly the case in this sad world that humane relationships based on co-existence or symbiosis cannot hold, and one group is pushed into a parasitic relationship with another.

In the midst of such a world, who can point their finger at a struggling family, locked in a fight for survival, and call them parasites?

It's not that they were parasites from the start. They are our neighbors, friends and colleagues, who have merely been pushed to the edge of a precipice.

As a depiction of ordinary people who fall into an unavoidable commotion, this film is:

a comedy without clowns,

a tragedy without villains,

all leading to a violent tangle and a headlong plunge down the stairs.

You are all invited to this unstoppably fierce tragicomedy.

Director BONG Joon Ho

Generally speaking, exogenous threats like wars or natural disasters act as pressure mechanisms forcing us to redouble our efforts to combat them together. The benefit of contagion is that the only way to combat it is to do less rather than more. That has some demonstrable advantages. There has been a dramatic global fall in carbon emissions. The only comparable reduction in greenhouse gases during the past 30 years came as the result of the decline of industrial production in eastern Europe after the fall of communism. That was managed exceptionally badly because neoliberal economists thought that what post-communist states needed was the pressure of free market competition. Shock therapy would galvanise the economy.

The pandemic has been a shock alright, but its effect has been the opposite of galvanising. People everywhere had to stop whatever they were doing or planning to do in the future. That provides an altogether different model of political change. The philosopher Walter Benjamin once noted that while Karl Marx claimed that revolutions were the locomotives of world history, things might actually turn out to be rather different: “Perhaps revolutions are the human race… travelling in this train, reaching for the emergency brake.”

“Just as the virus mutates, if we want to resist submission, we must also mutate”

“Contrary to what one might imagine, our health will not come from a border or separation, but only from a new understanding of community with all living creatures, a new sharing with other beings on the planet. We need a parliament not defined in terms of the politics of identity or nationality: a parliament of (vulnerable) bodies living on planet Earth. The Covid-19 event and its consequences summon us to once and for all go beyond the violence with which we have defined our social immunity. Healing and rehabilitation cannot be a simple negative gesture of social retreat, of the immunological closing of the community. Healing and care can only stem from a process of political transformation. Healing as a society would mean inventing a new community beyond the identity and border politics with which we have produced sovereignty until now, but also beyond the reduction of life to cybernetic biosurveillance. To stay alive, to maintain life as a planet, in the face of the virus, but also in the face of the effects of centuries of ecological and cultural destruction, means implementing new structural forms of global cooperation. Just as the virus mutates, if we want to resist submission, we must also mutate.”

Learning From The Virus

Paul B. Preciado

“Consent not to be a single being”

“Bodying as a verb reminds us that bodies are a field of forces through which individuations emerge and shift. How a body individuates depends on the circumstances of its surrounds, on the ecologies that compose it, here, now, on the histories that orient it, on the futurities that give it potential or unmoor it from the grounds of its participation in the world.

These orientations toward difference are pragmatic and operative. How a body becomes the body it is, here, now, the body it is identified to be, also depends on what it means to be a body, here, now, on the stakes of the form taking, on the limits of that form. Bodies are routinely obliterated at the very point where they individuate into this or that recognizable form. Much is at stake in the shape of individuation: there is no doubt that a continuous policing occurs that denies bodies the potential of their transitions, of their becomings, solidifying them from the outside into an identity that cannot be assimilated. I am thinking of the spas- tic body, of the disabled body, of the trans body, of the black body, of the lower caste body —there are so many who populate these unassimilable categories. What is important, I think, is to recognize that these captures are occurring because of the threat of bodying. What is terrifying is the very potential at the heart of bodying, the potential for a body to become, to shift, to alter the conditions of life-living, life in the register of the more-than, life beyond a dichotomy of the human and the nonhuman. To ask what kind of body our society needs is to take the operations of power seriously and to inquire, each time anew, how this body, how this neurodiversity, shifts the field of experience, shifts the terms of power/ knowledge.

Bodying is a process we all engage in. Usually, we become a body we already recognize, reproducing ourselves in the image we have come to associate as ours. This is particularly the case for those among us whose bodyings are least contested, those whose whiteness, whose neurotypicality already conforms to the mold of what a body should be. When Edouard Glissant incites us to “consent not to be a single being,” he is reminding us, I think, that the mold of that one form, that one body, should never suffice, that relations are what compose us, relations always in excess of the given, relations as the radically empirical

more-than that continuously refashions what it means to world.”

Me Lo Dijo un Pajarito

Neurodiversity, Black Life, and the University as We Know It

Erin Manning

Wouldn’t we tend to psychologically link our online life to the disease?

“I wonder how the relationship between offline and online is changing during the spread of the pandemic, and try to imagine the aftermath.

In the last thirty years, human activity has profoundly changed its relational, proxemic, cognitive nature: an increasing number of interactions have moved from the physical, conjunctive dimension—where linguistic exchanges are imprecise and ambiguous (thus infinitely interpretable), and any productive action consumes physical energies, as bodies get in touch in a flow of conjunctions—to the connective dimension, in which linguistic operations are mediated by computer ma- chines and therefore respond to digital formats. Any productive activity is partially mediated by automatisms, and people interact more and more densely although their bodies never meet. The daily existence of entire populations has been increasingly chained to electronic devices related to huge loads of data. Persuasion has been replaced by pervasion, as the psycho-sphere got innervated by the flows of the Info-sphere. The connection presupposes a hairless and dust-free accuracy. Computer viruses might interrupt or divert this accuracy, which does not know the ambiguity of physical bodies nor does it contemplate inaccuracy as a possibility.

Now, here it comes, a biological agent introduces itself into the social continuum, makes it implode, and forces it into inactivity. Conjunction, the sphere of which has been largely reduced by connective technologies, is the cause of contagion. Conjoining in the physical space has become the absolute danger that must be avoided at all costs. Conjunction must be actively prevented—don’t leave your house, don’t visit friends, keep a distance of two meters, don’t touch anyone on the street...

What we experience in these weeks is a huge expansion of the time spent online, and it couldn’t be otherwise because the emotional, productive, educational relationships must be transferred to the sphere in which one can not touch nor conjoin. Any sociality that is not purely connective ceases to exist.

And then? What happens next? What if this connection overload ends up breaking the spell?

I mean, sooner or later the epidemic will disappear (if this ever happens, they say in Italy it might happen on April 25th), wouldn’t we tend to psychologically link our online life to the disease? I imagine an explosion of a spontaneous caressing movement, inducing a substantial part of the younger population to shut down their connective screens, as reminiscent of this unfortunate lonely period?

I try not to take myself too seriously, but I do think about it.

“...the financial system is losing its grip: in the past, mathematical fluctuations determined the amount of wealth that everyone could have access to. Now, they no longer determine

anything. Now, wealth no longer depends on the money we have, but on what belongs to our mental life.”

Bifo - Diary of the psycho-deflation #2: “Normality must not return.”

Franco 'Bifo' Berardi charts the spiralling collapse of the social order under the ef- fects of COVID-19.

Discourse

(TRAUMA)

Coronavirus is our chance to completely rethink what the economy is for.

Malcolm Bull

The efforts of scientists, trying to establish a better understanding of our reality, show it to be a mutually coherent, densely connected system of influences. This is no longer just the famous “butterfly effect,” which as we know involves the way that minimal changes at the start of a process can lead in the future to tremendous, unpredictable results, but here we have an infinite number of butterflies and their wings, in constant motion― a powerful wave of life that travels through time. That is why I believe I must tell stories as if the world were a living, single entity, constantly forming before our eyes, and as if we were a small and at the same time powerful part of it.

Nobel Lecture by Olga Tokarczuk Nobel Laureate in Literature 2018

Extract of Happy Days

by Samuel Beckett